Remember the times when, as a kid, you were only allowed to go out to play if you had cleared up the chaos in your room first? While we might not have appreciated our parents’ persistence on the matter all too much back then (I sure did not), I think most people would agree - once they’re adults, that is - that it helped them with building good habits. Today’s post is a little bit like that parental insistence; a reminder to keep things tidy, or be it on our computers.

Minimalism vs Organization

A minimalist’s capsule wardrobe, perhaps.

A few years ago, Marie Kondo - Japan’s “Queen of clean” - had become popular outside Japan and seemingly everyone had suddenly subscribed to some form of “minimalism” as a lifestyle choice. On youtube, minimalist content creators fed the (at times curious, at times outright bizarre) trend of listing everything they own (e.g. here and here), #minimalism trended on twitter, the capsule wardrobe took over instagram by storm, and even Netflix produced a full-length movie entitled The Minimalists: Less is Now. Although the trend went quite far for some of its proponents, the director of said movie, minimalism youtuber Matt D’avella, recently reminded his followers that “they didn’t have to marry a minimalist” to be good people. Reassuring!

I, for my part, couldn’t wait to take this new-found panacea for all the world’s problems and apply it to my digital life. Devices like smart phones and computers are at the heart of most people’s professional as well as private lives and it is this constant exposure to them which makes me think that books like Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism deserve (at least) the same attention as the likes of Matt D’Avella or Marie Kondo. Not that there is anything wrong with decluttering the physical world around us - in fact, it has been eye-opening everytime I’ve done it.

Rather, I think that computers are a great place to experiment with structure. I have found that structure is the most useful tool when it comes to simplifying my life. At that, it is sometimes overlooked when we reduce minimalism to simply owning less stuff. It’s not only what we own (or how much of it), but also what we do with it - getting things done in other words. The way we assemble our possessions in the space around us affects how easily - and often - we will reach for and actually make use of them. Keeping things in an order that aligns well with our priorities and allows for easy and intuitive access is, thus, key to getting the most out of our belongings. Take for example a kitchen knive (I like to cook). You could of course store it anywhere, your garden shed or under your bed perhaps. But the fact that you will mostly need its services in the kitchen would make it a no-brainer to keep it in your kitchen drawer. Better yet, use a magnetic metal bar to “hang” it on your kitchen wall - in plain sight, that is. This choice maximises intuitive use, since the knive is always there when you need it, where you need it, if you need it. This can be applied to wardrobe organising, paper filing, and virtually all other life domains.

From wardrobes to computers

Above I rambled about how organization - situating the right tools in the right place for their easy use - is key to simplifying one’s life. It’s also key to getting things done efficiently on your computer. Say you are working on a new project for work. For me, this usually involves the accumulation of code, documents, data, and many different sub-directories over time. In the past, I have found that chaos is inevitable if I let this folder and file structure grow “organically” as I go. The worst part about this is that it makes automation a hustle. You cannot easily loop through different folders, for instance, if the files in them are not named consistently or if they are spread across different sub directories in an arbitrary way. Why then have I often ended up in situation like this? Frankly, because building a good folder structure for a project ex ante can, itself, be time-consuming. What follows is the best solution I have come up with so far. It is far from perfect and I encourage you to experiment with it and share your strategies.

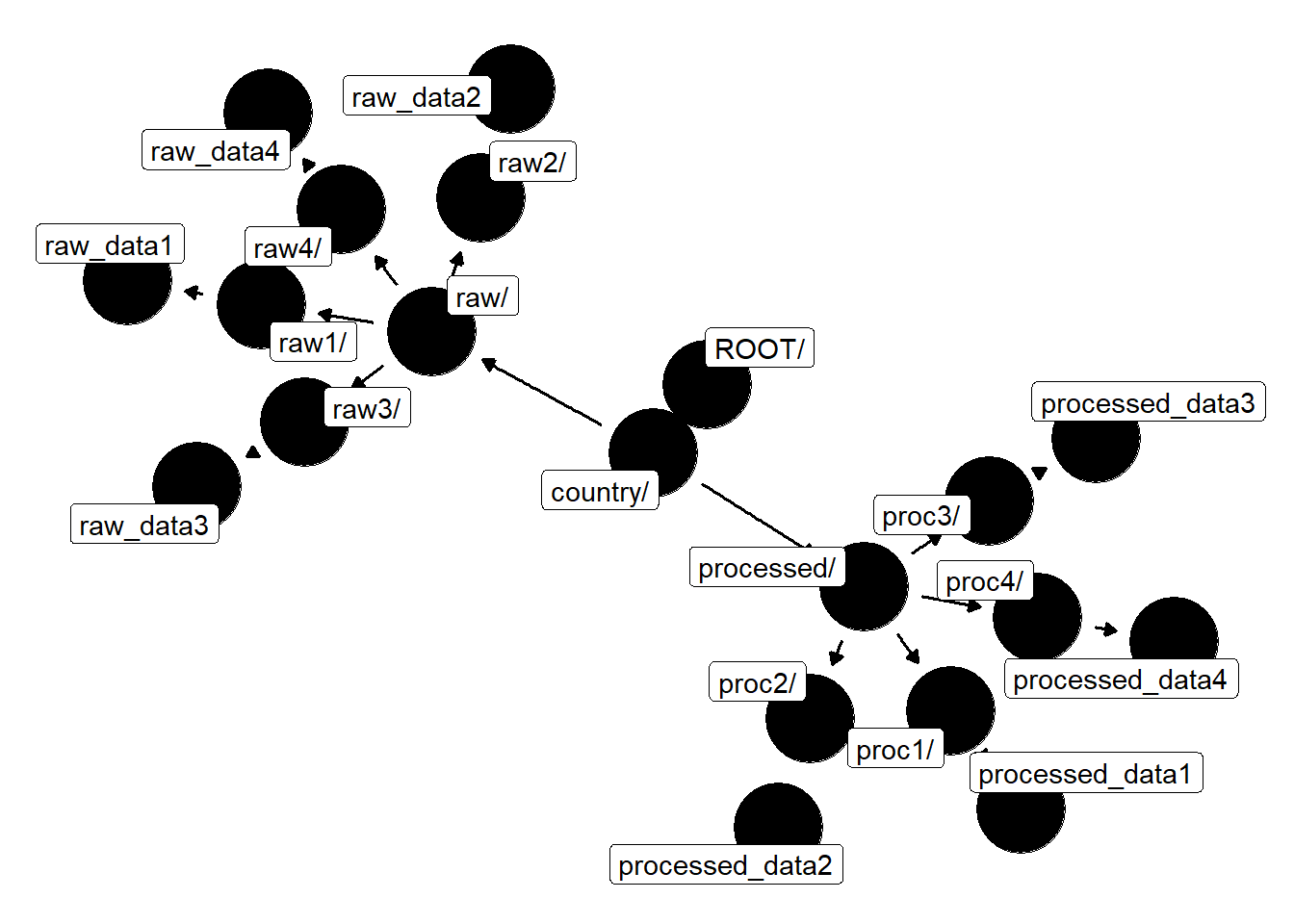

Recently, I had to save, clean, and re-save household data for more than fifty countries. For each of them, I saved four different kinds of datasets for all the years available. In the end, the file and folder structure I was aiming for looked like this graph. First, find the ROOT/ folder. Then follow the arrows to explore the nested structure.

Figure 1: An example of a project folder structure.

The ROOT/ folder includes a ROOT/country/ folder. In it are, in turn, two folders: raw and processed. ROOT/country/raw/ is where the original, unprocessed data goes initially. It is itself partitioned into folders, one for each of four types of data. The data wrangling and cleaning script(s) take data from there and output the processed datasets to ROOT/country/processed/, according again to the data types (1 thru 4). This is the clean data that enters my analysis.

Can we bash it, already?

Alright, to start with you need to know that the bash command to make new directories is conveniently called mkdir. To create a new folder called things on your desktop is as easy as writing…

cd desktop

mkdir thingsTo create a subdirectory inside things/ - let’s call it things/stuff/ - we could use the same principle: just cd into things/ and create the new sub-directory.

cd desktop

mkdir things

cd things

mkdir stuffThis is an example of the ad-hoc approach to creating a file system; everytime I feel like I need a subfolder inside a directory, I just go there, create it and place files in it. But this becomes cumbersome very fast, especially because one has to cd in and out directories all the time. Thankfully, there is a way to nest folders inside the mkdir command. The following lines create the same directory desktop/things/stuff/ as before, but this time in one line using the flag -p to allow for a nested structure.

cd desktop

mkdir -p things/stuffNext, let’s say that we want to divide our belongings into some things and other things, both of which consist of stuff and more stuff. For this, we use curly braces. Also make sure to use string delimiters (either ' or ") around directory names that include spaces.

cd desktop

mkdir -p {'some things','other things'}/{stuff,'more stuff'}We just created a nested folder structure with multiple folders at each level. To see how truly powerful this simple command is, let’s finally create the project folder structure from figure 1. To up the complexity a little, the code below creates not one, not two…but fifty-five such country folders (named according to their two-letter country codes) inside the \ROOT directory.

cd ROOT # go to directory

mkdir -p {al,am,bd,bj,bo,bf,bi,kh,ci,cm,cf,km,cg,eg,et,ga,gm,gh,gt,gn,gy,ht,hn,jo,kz,ke,kg,ls,lb,mg,mw,mv,ml,md,ma,mz,np,ni,ne,ng,pk,py,pe,rw,st,sn,sl,tz,tl,tg,tr,ug,ua,ye,zm,}/{processed,raw}/{type_1,type_2,type_3,type_4}This works but it is rather messy to look at. If you need to access and rerun this several times, it might be wise to write a shell script and use \ to allow commands to run over multiple lines in bash. Then you can also use # to add comments to your code.

cd ROOT # go to directory

mkdir -p {\ # initiate mkdir

al,am,bd,bj,bo,bf,bi,kh,ci,cm,cf,\ # add country folders

km,cg,eg,et,ga,gm,gh,gt,gn,gy,ht,\

hn,jo,kz,ke,kg,ls,lb,mg,mw,mv,ml,\

md,ma,mz,np,ni,ne,ng,pk,py,pe,rw,\

st,sn,sl,tz,tl,tg,tr,ug,ua,ye,zm,\

}\

/{processed,raw}\ # create processed and raw sub-folders inside each country

/{type_1,type_2,type_3,type_4} # divide them into data typesLet’s rewind a bit. This one (admittedly long) command creates 55 folders, each of which contains two folders, each of which contains four folders. Multiply and you get 440 folders, embedded in a pre-defined and consistent structure. I don’t know about you, but I was awe-struck by that kind of efficiency.

Coupled with a little planning ahead, you can now create usable nested project directories in the blink of an eye. Integrating a script like this to your computing routines can boost your productivity and makes it easier for others, who are unfamiliar with your folder structures, to replicate your work.